How Do I Talk to Somebody Who Just Doesn’t Believe Basic Facts?

Author:

Vanessa Otero

Date:

11/05/2024

The number one question I get when doing public talks about Ad Fontes and the Media Bias Chart is this:

How do I talk to somebody who just doesn’t believe basic facts?

Talking to people on the opposite side of the political spectrum has gotten especially frustrating in the last 10 years or so. The height of frustration often occurs right before and right after an election. Our media ecosystem has become so fragmented, and people increasingly live in different information bubbles. We often see our political opponents as people who don’t share the same factual understanding of the world, and in many cases, that is true.

We can have conversations that make a difference. Here are my tips for decreasing your frustration and increasing your effectiveness when having a conversation, whether it is about election results or about politics generally. The short version is:

- Ask questions to figure out where they are.

- Decide whether it is worth it to engage.

- Set a reasonable goal for the conversation.

- Get specific. Don’t try to take on all of politics at once.

- Share your experiences or new information.

- Ask what they think about what you just shared with them.

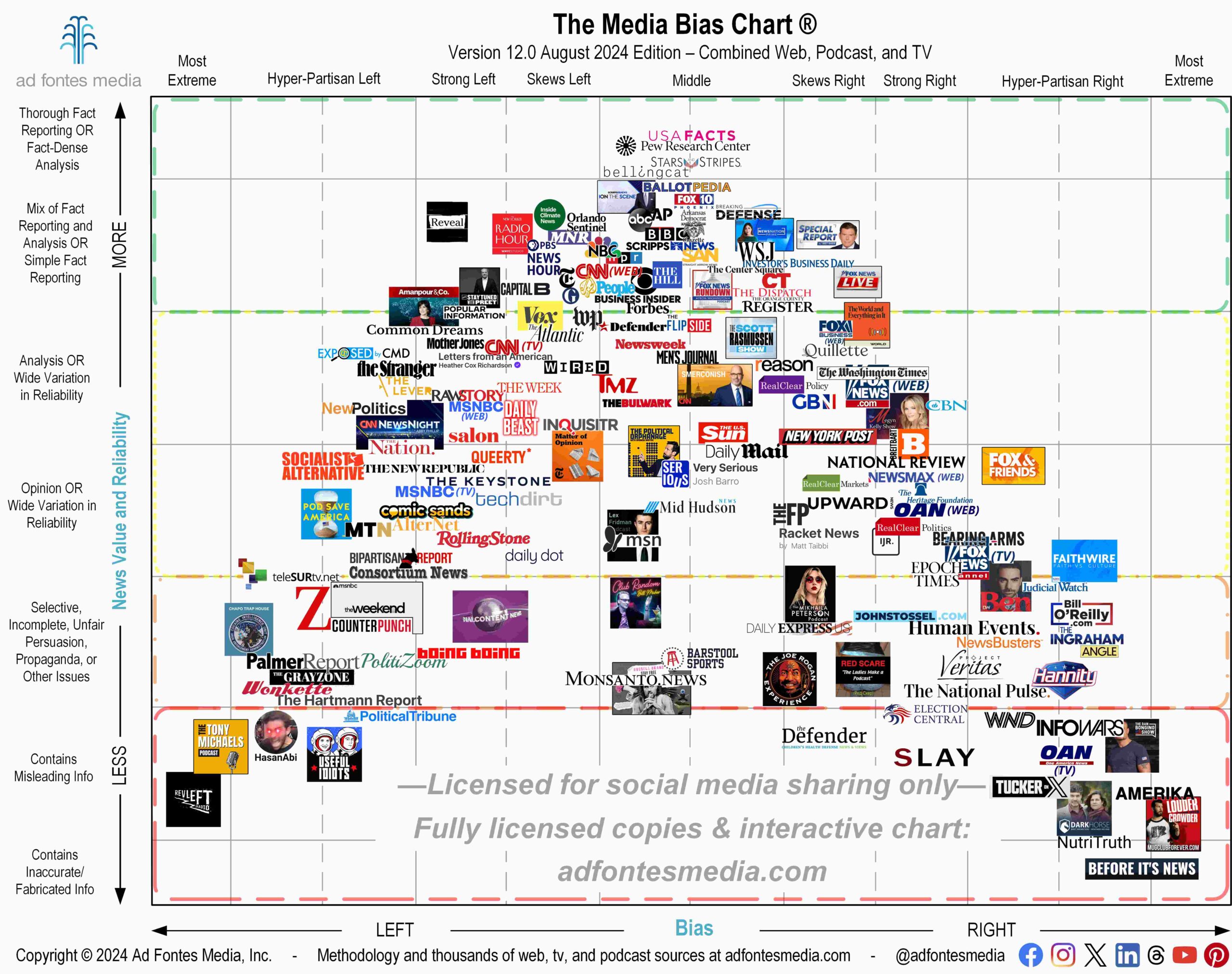

1. Start by figuring out exactly where the person you are talking to is from a media-consumption perspective. A good mental model is trying to figure out where you would place them on the Media Bias Chart® based on the media they consume.

Not everyone is in the same spot! It’s not enough just to say that someone “doesn’t believe basic facts.” Are you talking to someone who disagrees on what economic policies lead to lower prices, or are you talking to someone who thinks the earth is flat? There’s a big range between those things.

How do you figure out where they are? Ask them questions.

Ask questions about why they believe what they believe. About what is important to them. And about what they typically watch, read, and listen to. Don’t just ask “where do you get your news?” because most people won’t recall everything they consume immediately. Ask about podcasts, YouTube channels, any websites they like to visit, what they watch on TV, etc.

Asking questions accomplishes several things. First, it’s not inherently confrontational, like starting out with assertions about what you think is right. Second, it makes people feel heard, and makes them feel like you care. People like talking about what they think and what is important. Third, it gives you real answers to what they actually think and what news they consume, which is way more valuable than your assumptions.

Mentally placing them on the chart is especially helpful because in this era of polarization, we tend to think people on the other side are all pretty much the same. We see the nuance in positions between people on our side, but we assume people on the other side are all the same because their resulting vote is the same. In polarization literature, this phenomenon is referred to as “outgroup homogeneity.”

2. Once you figure out where that person is, determine whether it is worth your time, energy, and sanity to try to have a conversation with them. Sometimes it is not worth it. The primary consideration in whether it is worth it is not where they are, but rather your own capacity to have the conversation no matter where they are.

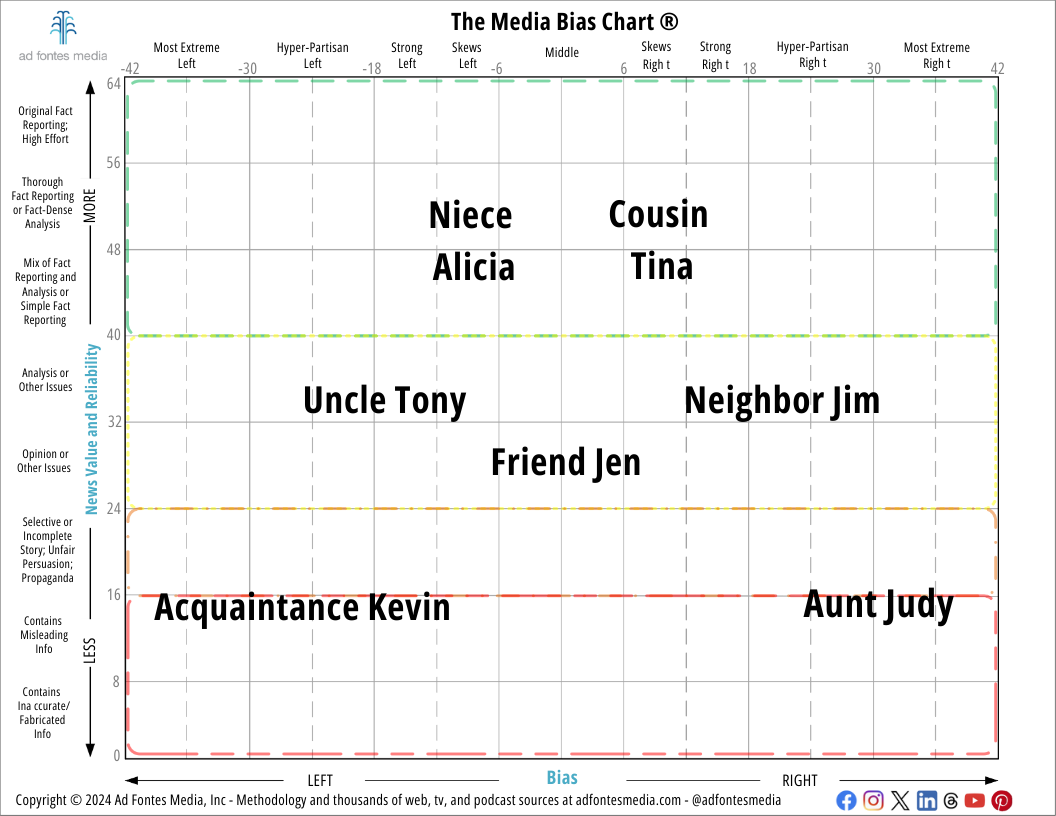

If you are full of energy to engage with Acquaintance Kevin, go for it. But if you feel too angry, too tired, or ill-equipped to have a conversation, or if you think it would damage a relationship that is important to you, release yourself from the guilt of having to have the conversation.

3. If you have decided to engage in a conversation, set a conversation goal for yourself that is reasonable based on where the other person is.

If they are undecided, middle, and don’t really follow politics closely (Friend Jen in this chart example), convincing them to vote is often a highly achievable goal. Undecideds and infrequent voters are often open to your reasons!

If they just slightly lean to one side or another, and they consume mostly reliable information, convincing them to change their mind on an issue might be a reasonable goal.

If they are farther to the left or right (like Neighbor Jim or Uncle Tony in this example), it is less likely that you will convince them to completely change their mind on an issue. But you might be able to get them to soften their position a bit. A reasonable goal might simply be to share a new perspective with them.

If they are way down the rabbit hole on one side or another, your goal may just be to try to get them to see how the information they consume is creating some undesirable outcomes in their life (like being really angry all the time, or having trouble communicating with family and friends). Another goal might be to share one or two information literacy or critical thinking concepts, like lateral reading and why large conspiracies are often improbable.

Remember, for people who are really entrenched in their beliefs, there are a lot of other forces that have shaped their thinking over time. You might talk to them for 30 minutes, but afterward they will likely continue consuming their regular diet of partisan and/or social media, which has a lot of influence.

Make the difference you can, even if you can’t fix everything.

4. Get specific. The more granular you can get about one media source, one claim, or one issue, the likelier you can find some agreement. If you argue about broad narratives and big topics, like “how the media is” or “how the Democrats are,” it’s likely that the other person will talk about broad narratives and big topics, too. So much opinion, and so many assumptions, are baked into broad statements, which makes it hard to prove anything about them in a conversation.

Express your goal to talk about things specifically rather than broadly.

If someone wants to talk about a policy, focus on that policy. If someone wants to talk about the media, narrow it down to one media source, or even one article or episode. If you are disputing a fact, statistic, or what actually happened, the best thing you can do is stop and look something up together, rather than flatly asserting, “Well I know it’s this way.”

5. There are two kinds of sharing that can make a difference in a conversation:

- Sharing your personal experience and how it makes you feel.

- Sharing new information they may not have heard before.

Nothing is more persuasive than authentically sharing your personal experience and why it impacts your beliefs. But sharing new information is compelling, too; if someone consumes a lot of partisan content on their side, they typically don’t hear the most compelling arguments on your side.

6. Ask what they think about what you just shared with them.

When someone changes their mind, it usually doesn’t look like them admitting, out loud, “I was wrong and you are right!” It usually takes place through reflection and a softening of their initial position. You might not even see how someone changes their mind until much later, if ever. But asking people what they think encourages reflection and creates the space for changing their minds, and it’s the most effective thing you can do to truly influence people.

Want to stay informed on all of the work of Ad Fontes Media? Sign up for our free biweekly email newsletter!

Vanessa Otero is a former patent attorney in the Denver, Colorado, area with a B.A. in English from UCLA and a J.D. from the University of Denver. She is the original creator of the Media Bias Chart (October 2016), and founded Ad Fontes Media in February of 2018 to fulfill the need revealed by the popularity of the chart — the need for a map to help people navigate the complex media landscape, and for comprehensive content analysis of media sources themselves. Vanessa regularly speaks on the topic of media bias and polarization to a variety of audiences.