The Information Ecosystem, The Election, and Why ‘Trust in the Media’ is the Wrong Question

Author:

Vanessa Otero

Date:

11/11/2024

Lots of things I could say about the election.

Today I just want to talk about our information ecosystem’s role in it.

I don’t like generalizations, so I especially dislike when people try to attribute the binary end result of a complex process to simple causes. For the election, there isn’t one reason he won and she lost. There are dozens of major reasons and millions of individual ones.

But I do want to talk about some of the major factors for the outcome I am most familiar with. These are:

- Polarized realities

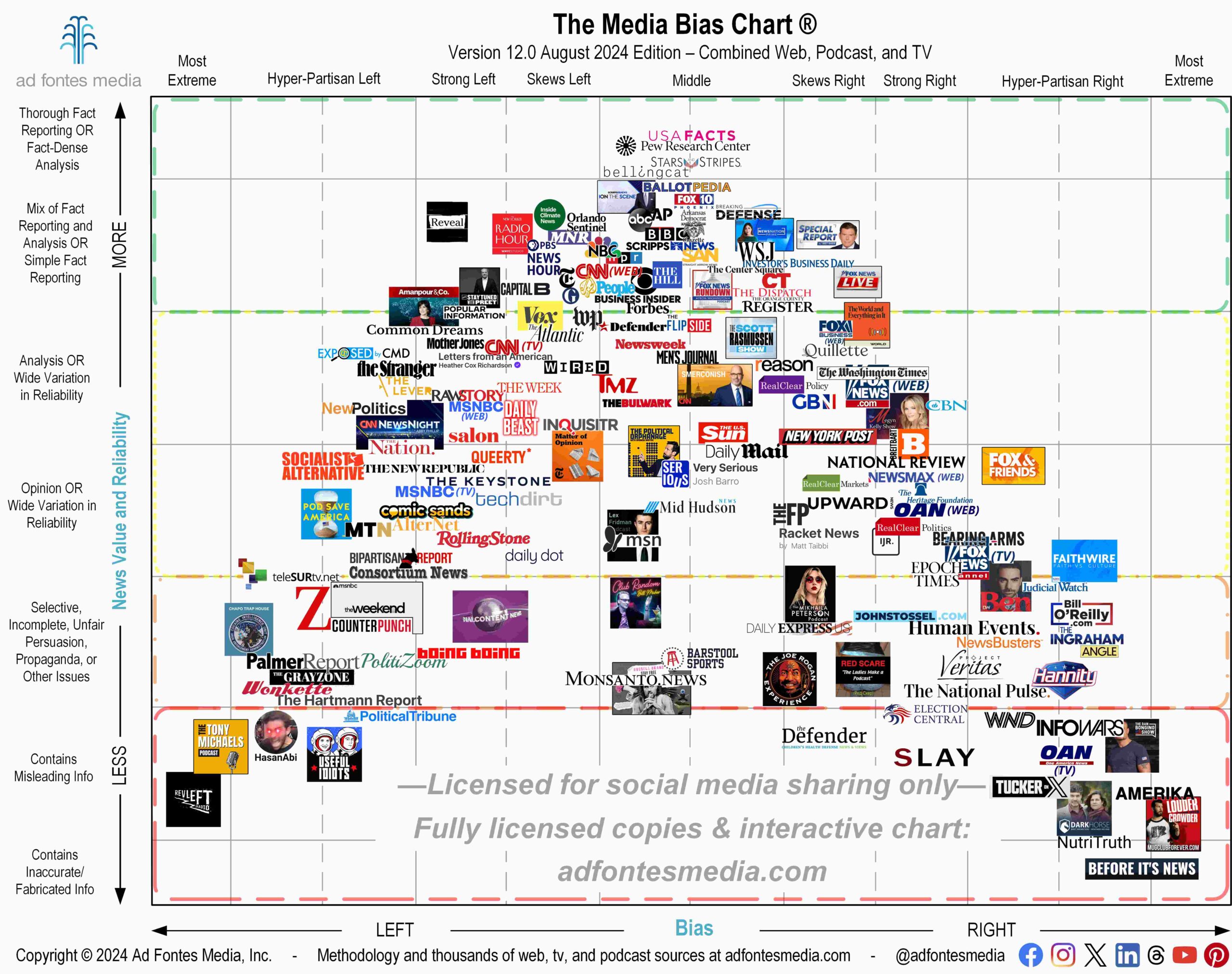

- The extreme fragmentation of the media ecosystem, exacerbated by social media algorithms, which results in information silos/filter bubbles

- The proliferation of opinion, propaganda, misleading, false, and extremely biased content within some of those silos

- The separation of true and fact-based information from some of these silos

Yes, these factors played an impossible-to-quantify role in the results of the election, but beyond that, they are also drivers of an ongoing problem we all recognize right now: namely that we are polarized not merely on policies but on reality itself.

The difference in reality is so stark that about half the voting population is devastated, sickened, and frightened by the result, and the other half is overjoyed and optimistic about it, and it’s hard for us to operate as political problem-solvers, co-workers, neighbors, family members, or friends in this state.

And of course I want to talk about potential solutions because that is just who I am, and because I can’t stand our collective tendency to spend way more time admiring the problems than trying to build solutions. I swear, the next person who sends me a poll stating the most banal and tired and known fact of our era, that “trust in media is at an all-time low” is going to get a profane earful from me. We fucking know.

After 20-plus years of asking ”do you trust the media,” when referring to the top 50 most familiar news brands, it’s clear that has been the wrong question for at least the last 10 years. “The media” is not one thing, and it is a very different thing than it was 20 years ago. The large newspapers and TV news outlets that existed 20 or more years ago have spent the last 20 years responding to these “do you trust the media” polls by naively asking “what can we do to increase trust in us?” when the things that led to their trust declines had way more to do with external technological forces than the things they printed or broadcasted. Individual newsrooms at these outlets trying to solve for declines in trust are like individual teachers trying to solve for young people’s declining mental health. Sure, you can do your best in your role, but the causes are more systemic.

“Traditional” media, meaning resource-intensive local and national newspapers and cable and network broadcast news, has been outstripped in terms of audience size and influence by the universe of news and information content created outside of it, which is largely produced at much lower cost. “The media” is just as much YouTube channels and podcasts and Substacks as it is the top 50 most familiar news brands. Asking people if they trust “the media” is like asking people if they trust “politics.” What are you even asking them about?

“What people trust” and “what is true” are often not the same thing. People trust liars all the time. People trust cult leaders. PEOPLE TRUST THE MEDIA THEY PERSONALLY CONSUME, irrespective of how true or false it is. “Do you trust something” is highly subjective, almost wholly dependent on who you ask.

“Is this thing true” can be determined more objectively (Philosophy/Epistemology 101 detour–although there may not be “one objective truth,” most things can be evaluated for whether they are more true or less true than other things, or for whether they are certain or uncertain, or knowable or unknowable).

The best way to tell if something is true is by evaluating evidence and likelihood. But that’s hard to do, especially when there is too much information and a lot of it is conflicting. So people use shortcuts to determine “what do I trust,” and those shortcuts can include things like:

- Do I like/feel connected to the person/outlet delivering the information?

- Do they have an existing good reputation with me?

- Are they telling me what I want to hear?

- Are they big? Are they small?

- Do I think this person/outlet has the correct incentives to tell me the truth?

- Do people around me believe what they are saying?

These shortcuts lead to a highly subjective and error-prone decision making process of what to trust, and a divergence between what people trust and what is true. Even people who end up trusting reliable sources sometimes end up there by luck rather than their skill in evaluating evidence.

There are thousands of new and old media sources competing for our attention and trust, and each of them have had some success capturing some segment of us. We’ve gotten shoved into our corners of the information ecosystem through a combination of habits, algorithms, confirmation bias, which lock us into hard-to-escape bubbles. This is problematic because in a significant number of these bubbles, the information circulated within is full of falsehoods and hyper-partisan vitriol. Further, reliable and fact-based information don’t get into them. The well-reported journalism piece is the tree falling in the forest that people in other bubbles don’t hear.

There is a lot more to say about the structure of this ecosystem–whole books like Invisible Rulers by Renee DiResta–but the reason this info-bubble structure causes societal dysfunction is because people end up making decisions based on wrong information of varying importance. Sometimes it makes people believe Trump said a thing he didn’t, or Harris didn’t have a policy she did, or that Trump’s assassination was staged, or that Joe Biden stole the previous election, or that Elon Musk helped steal this one. The extent to which a particular falsehood gets believed varies, to say the least.

What is the cumulative effect of all that wrong information on the election outcome? Impossible to quantify, but we can see individual negative effects of making decisions based on wrong information in general, and in the frustrating conversations we have with each other in real life.

At this point, it should be apparent that it is not just untrue and highly biased information that is the problem–it’s the structural entrenchment thereof as well. Technology giants have contributed much to the problem and need to be part of enabling its solutions.

Our core function at Ad Fontes Media is rating the news, but our problem-solving focus in the coming months and years will be around:

- Continuing to identify and structurally ensure the success of reliable, fact-based news and information in all its formats old and new, large and small

- Educating people about the information ecosystem itself

- Encouraging Intentional focus by individual people, news outlets, and businesses, and technology companies on puncturing information bubbles, which includes both:

- Seeking out what is in other people’s bubbles and

- Getting good information seen in the places it currently isn’t, at scale

Much more to come.

Want to stay informed on all of the work of Ad Fontes Media? Sign up for our free biweekly email newsletter!

Vanessa Otero is a former patent attorney in the Denver, Colorado, area with a B.A. in English from UCLA and a J.D. from the University of Denver. She is the original creator of the Media Bias Chart (October 2016), and founded Ad Fontes Media in February of 2018 to fulfill the need revealed by the popularity of the chart — the need for a map to help people navigate the complex media landscape, and for comprehensive content analysis of media sources themselves. Vanessa regularly speaks on the topic of media bias and polarization to a variety of audiences.